The 5 key factors to consider in an exercise program

Developing a sound, individually tailored exercise program is one of the steps recommended to help improve your client’s general physical and psychological well-being. This is regardless of whether they are at risk of developing lymphoedema or actually have it. The goal is to address five key factors to ensure a suitable program is established for your client. This may mean that you need to call upon the skills of a variety of health professionals if it’s beyond your scope of practice.

When you initially discuss exercise with your clients, images of working out in the gym on a treadmill or lifting weights might come to their mind. We need to educate them that engaging in physical activity to sustain or improve health and fitness can be manageable. They need to see how it can be incorporated easily in their everyday routine.

When structuring an exercise program for your lymphedema client, the five key factors you need to consider are:

- Range of movement

- Strength

- Fitness

- Osteoporosis

- Weight control

1. Range of Movement

Programs that address individual range of movement assist your client in having the best chance to regain their mobility after cancer surgery.

Important areas to remember are:

- Previous musculoskeletal issues.

- Scars and making sure they are not impeding the movement of the skin. Watch how the skin moves around these areas when the client moves their limb.

- Muscle tightness and weakness.

- Tight skin after radiotherapy.

- Impact of oedema on movement.

- Clients goals and expectations

- Functional range of movement.

- Management of Axillary Web Syndrome (AWS) or cording if it’s after breast cancer surgery.

Klose Training has an excellent online module on AWS. This online course describes the clinical presentation of AWS, outlines possible causes, and recommends current therapeutic options for this condition. The course format includes numerous video segments of patients with AWS, common exercises, and treatment techniques to use in your practice.

2. Strength

There is strong evidence that progressive strengthening exercises are safe in the breast cancer population. I believe that it is essential that our clients are monitored as they progress these exercises either, as part of a lymphoedema surveillance program, or if they have lymphoedema, as part of their lymphoedema management program.

Kathryn Schmidt has completed vast amount of research in this area and her Strength After Breast Cancer program is a comprehensive online program. This program is based on the Physical Activity and Lymphedema (PAL) Trial which assessed the safety and efficacy of slowly progressive weightlifting for breast cancer survivors with or at risk for lymphedema. This online course provides all the materials needed to set up the program in your own facility.

For other forms of cancer, the level of evidence is not as strong and further research is required. But what we know from the breast cancer arena can inform strength programs for other forms of cancer.

The following are recent research papers that you might find interesting.

click on abstract title below to open

Effects of Supervised Multimodal Exercise Interventions on Cancer-Related Fatigue: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. (Meneses-Echávez, González-Jiménez, and Ramírez-Vélez 2015)

Authors: José Francisco Meneses-Echávez, Emilio González-Jiménez, and Robinson Ramírez-Vélez

Source: BioMed Research International Volume 2015

Abstract:

Objective. Cancer-related fatigue (CRF) is the most common and devastating problem in cancer patients even after successful treatment. This study aimed to determine the effects of supervised multimodal exercise interventions on cancer-related fatigue through a systematic review and meta-analysis. Design. A systematic review was conducted to determine the effectiveness of multimodal exercise interventions on CRF.Databases of PubMed, CENTRAL, EMBASE, and OVID were searched between January and March 2014 to retrieve randomised controlled trials. Risk of bias was evaluated using the PEDro scale.

Results. Nine studies (𝑛 = 772) were included in both systematic review and meta-analysis. Multimodal interventions including aerobic exercise, resistance training, and stretching improved CRF symptom s(SMD = −0.23;95%CI:−0.37to−0.09;𝑃 = 0.001). These effects were also significant in patients undergoing chemotherapy (𝑃 < 0.0001).Non significant differences were found for resistance training interventions (𝑃 = 0.30). Slight evidence of publication bias was observed (𝑃 = 0.04). The studies had a low risk of bias (PEDro scale mean score of 6.4 (standard deviation (SD) ±1.0)). Conclusion. Supervised multimodal exercise interventions including aerobic, resistance, and stretching exercises are effective in controlling CRF. These findings suggest that these exercise protocols should be included as a crucial part of the rehabilitation programs for cancer survivors and patients during anti cancer treatments.

This article reviewed nine randomised controlled trials over a short time range in 2014 and the main outcomes from this paper are:

- Supervised exercise is safe and beneficial for cancer survivors through strengthening programs by health professionals.

- Personalised supervision can optimise patient’s adherence to and compliance with interventions.

click on abstract title below to open

Effects of compression on lymphedema during resistance exercise in women with breast cancer-related lymphedema: a randomized, cross-over trial. (Singh B, Newton RU, Cormie P, Galvao DA, Cornish B, Reul-Hirche H, Smith C, Nosaka K, Hayes SC 2015)

Authors: Singh B, Newton RU, Cormie P, Galvao DA, Cornish B, Reul-Hirche H, Smith C, Nosaka K, Hayes SC

Source: Lymphology [Lymphology] 2015 Jun; Vol. 48 (2), pp. 80-92.

Abstract:

The use of compression garments during exercise is recommended for women with breast cancer-related lymphedema, but the evidence behind this clinical recommendation is unclear. The aim of this randomized, cross-over trial was to compare the acute effects of wearing versus not wearing compression during a single bout of moderate-load resistance exercise on lymphedema status and its associated symptoms in women with breast cancer-related lymphedema (BCRL). Twenty-five women with clinically diagnosed, stable unilateral breast cancer-related lymphedema completed two resistance exercise sessions, one with compression and one without, in a randomized order separated by a minimum 6 day wash-out period. The resistance exercise session consisted of six upper-body exercises, with each exercise performed for three sets at a moderate-load (10-12 repetition maximum). Primary outcome was lymphedema, assessed using bioimpedance spectroscopy (L-Dex score). Secondary outcomes were lymphedema as assessed by arm circumferences (percent inter-limb difference and sum-of-circumferences), and symptom severity for pain, heaviness and tightness, measured using visual analogue scales. Measurements were taken pre-, immediately post- and 24 hours post-exercise. There was no difference in lymphedema status (i.e., L-Dex scores) pre- and post-exercise sessions or between the compression and non-compression condition [Mean (SD) for compression pre-, immediately post- and 24 hours post-exercise: 17.7 (21.5), 12.7 (16.2) and 14.1 (16.7), respectively; no compression: 15.3 (18.3), 15.3 (17.8), and 13.4 (16.1), respectively]. Circumference values and symptom severity were stable across time and treatment condition. An acute bout of moderate-load, upper-body resistance exercise performed in the absence of compression does not exacerbate lymphedema in women with BCRL.

Twenty-five women with clinically diagnosed, stable unilateral breast cancer-related lymphedema completed two resistance exercise sessions, one with compression and one without.

There was no difference in lymphedema status for bioimpednace pre- and post-exercise sessions or between the compression and non-compression condition. Circumference values and symptom severity were stable.

The sample size is small and further research is required before concluding that moderate-load, upper-body resistance exercise, performed in the absence of compression, does not exacerbate lymphedema in women with BCRL.

3. Fitness

When we have the discussion with our clients about fitness, we need to clearly assess their current level of fitness. If this assessment is undertaken when they have already commenced their cancer treatment, then a pre cancer fitness level should be ascertained. It is also essential to get an understanding of what their goals are in relation to fitness. It is well known that individuals are more likely to continue with fitness programs if they enjoy it.

For many that can be simply implementing a walking program. Walking is great as they can do it anytime and they can motivate themselves by using a pedometer to count the number of steps.

For others they may want to commence or return to various forms of sport. Once again there is increasing evidence supporting that they can safely do this whether they are at risk of lymphoedema or already have lymphoedema.

click on abstract title below to open

A Randomized Trial on the Effect of Exercise Mode on Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema. (Buchan , Janda , Box, Schmitz , & Hayes, 2016

Authors: Buchan, J., Janda, M., Box, R., Schmitz, K., Hayes, S.

Source: American College of Sports Medicine. Article in press 2016)

Abstract:

Purpose: Breast cancer-related lymphedema is a common and debilitating side effect of cancer treatment. This randomized trial compared the effect of progressive resistance- or aerobic-based exercise on breast cancer-related lymphedema extent and severity, as well as participants’ muscular strength and endurance, aerobic fitness, body composition, upper-body function and quality of life.

Methods: Women with a clinical diagnosis of stable unilateral, upper-limb lymphedema secondary to breast cancer were randomly allocated to a resistance- (n=21) or aerobic-based (n=20) exercise group (12-week intervention). Women were assessed pre-, post- and 12 weeks post-intervention, with generalised estimating equation models used to compare over time changes in each group’s lymphedema (two-tailed p<0.05).

Results: Lymphedema remained stable in both groups (as measured by bioimpedance spectroscopy and circumferences), with no significant differences between groups noted in lymphedema status. There was a significant (p<0.01) time by group effect for upper-body strength (assessed using 4-6 repetition maximum bench press), with the resistance-based exercise group increasing strength by 4.2 kg (3.2, 5.2) post-intervention compared to 1.2 kg (-0.1, 2.5) in the aerobic-based exercise group. Although not supported statistically, the aerobic-based exercise group reported a clinically relevant decline in number of symptoms post-intervention (-1.5 [-2.6, -0.3]), and women in both exercise groups experienced clinically meaningful improvements in lower-body endurance, aerobic fitness and quality of life by 12-week follow-up.

Discussion: Participating in resistance- or aerobic-based exercise did not change lymphedema status, but led to clinically relevant improvements in function and quality of life, with findings suggesting that neither mode is superior with respect to lymphoedema impact. As such, personal preferences, survivorship concerns and functional needs are important and relevant considerations when prescribing exercise mode to those with secondary lymphedema. © 2016 American College of Sports Medicine

This article compared a strength training program with an aerobic program. Both programs did not change lymphedema status, but led to improvements in function and quality of life, with findings suggesting that neither mode is superior with respect to lymphoedema impact.

4. Osteoporosis

As you may be aware some of the cancer treatment regimens have the side effect of reducing bone density. This can impact both men and women. But for women, who are tipped into menopause with treatment or who are currently in menopause, the risk of osteoporosis development may be increased.

As health professionals, it is important to stay up to date with current information on osteoporosis and it management. There are a number of good web sites in particular www.osteoporosis.org.au which has excellent resources that can be found at http://www.osteoporosis.org.au/resources

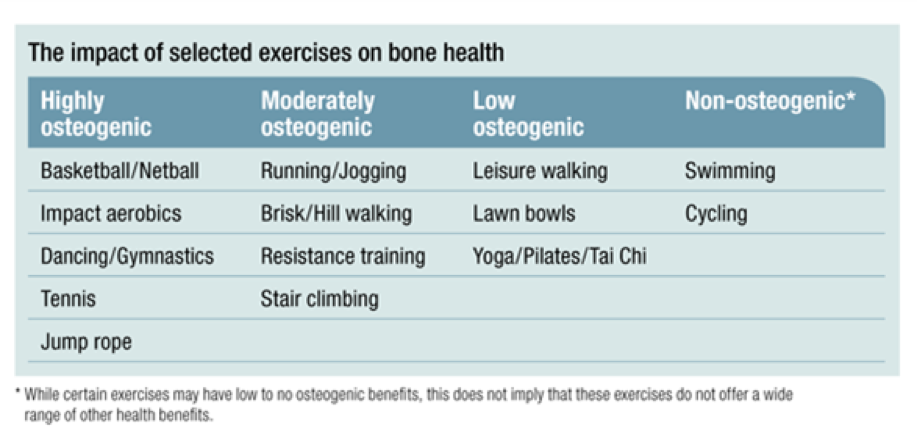

When developing exercise programs for our clients we should also include exercises that promote strengthening our bones. Osteoporosis Australia has an interesting table shown below. Obviously not all our clients can play netball or basketball but they can add into their walking routine some hills or some steps. They have a useful exercise and bone density fact sheet and a fact sheet for osteoporosis and breast cancer.

Taken from www.osteoporosis.org.au/exercise

5. Weight control

The effects of obesity are far reaching. We are well aware that it can increase the risk of developing lymphoedema after cancer treatment and for those that have lymphoedema it can exacerbate it and make it more difficult to manage.

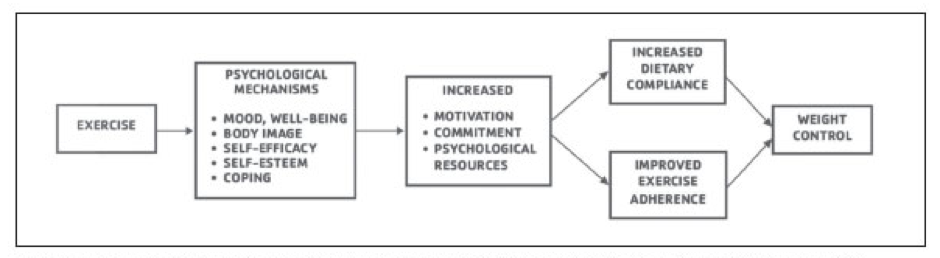

The good news is there is growing evidence that exercise induces changes in mood, body image, self-efficacy, and coping leading to increased physical activity, improved eating, and weight loss.

There are significant effects of exercise-induced mood change on weight loss and psychosocial predictors of weight loss. Emotion- triggered eating can be regulated by the effects of mood change that occurs with exercise.

Annesi J. Supported exercise improves controlled eating and weight through its effects on psychosocial factors: Extending a systematic research program toward treatment development. Permanente Journal. 2012. Vol 16.

Exercise should be moderate intensity and the Heart Foundation has a handout that has guidelines and tips for various age groups. The key message is

Over to you

Encouraging, educating and supporting your clients to get up and active involves consideration of their range of movement, strength, fitness, osteoporosis and weight control. You may have developed your own program or, if outside your scope of practice, referred to other health professionals.